Time by Shahzad Shamim (guest writer)

|

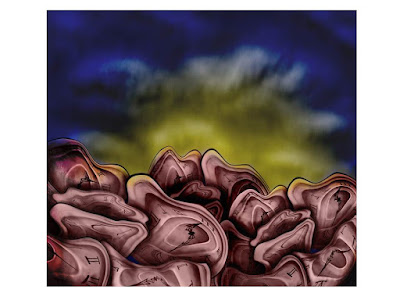

| Illustration / Photo-credit: Saniya Kamal [inspired by Dali's 'persistence of memory'] |

“How much time do I have?”

Very

few fortunate brain tumor patients (such

an oxymoron) had the sad opportunity of asking this themselves. Most of

the time the question was asked by someone from the family. But the question always

came up, so it was by no means unexpected. But much earlier than I expected. Or

liked. How I dreaded answering it.

He

was 35, tall for his ethnic background but still short for the global average.

Brownish, medium weight when I first met him, but much lighter now after all

the ‘treatments’ he had received. He was part of the country’s shrinking

educated, middle class, an engineer working for a local firm, apparently doing

really well. With him used to be his wife, a pretty girl, a few years younger and

a mother of two, a boy and girl, neither older than three. The wife hardly ever

participated in the discussions. I once met his parents too, but they too did

not talk much. He did all the talking. When we first met, in my tiny

Neurosurgery clinic a few months ago, he appeared anxious, no… terrified.

After

his surgery, there was obvious relief, perhaps as a consequence of the mistaken

assumption that the worst had passed away. Now once again, I see him in a

different mood altogether. He was neither anxious, nor afraid. He was tired.

"How much time do I

have?”

I

knew the answer. I could answer the question, without answering it. Or, I could

choose not to answer the question, even when answering it in detail. That is my

privilege as a physician.

So,

how am I to answer this all-important question? Do I tell him that he has a

rapidly enlarging brain tumor, which has recurred despite all forms of

‘advanced’ treatment that decades of research have arrived at? Decades of

research worth a billion dollars, which benefited a generation of researchers, students, universities, and of

course, numerous drug company workers. But has the research benefited any

patients? Only a very few, giving them a few more weeks to live….or a few more

weeks to die.

Do

I tell him that it should not matter to him anyway because in a few weeks time,

he will lose all perception of time, persons, and even reality.

Or

do I tell him to go home. Go home and start preparing for the final journey, to

a place, which may or may not exist, depending on his belief. Go home and tell

his wife that he loves her…that he loved her. And then tell

her about all the loans he had to take to afford this treatment hoping that he

would one day return it all, but will now have to pass on to his wife.

She will need to find an extra job. Her children will have to cancel their

plans for vacations, or their desire for one. He lost this gamble and his wife

will have to pay for it. But then he knew the stakes were high. His doctor had

told him there might be a treatment. Might.

Do

I say go home to his little boy and girl, hug and kiss them, before he stops recognizing

them. Give them his life’s worth of experience and advice. He has learnt so

much in his life and it is all stored in his memories. Now that he will lose

his memory, the information has to be transferred elsewhere. And

when I do tell him how much time he has left, do I look him in the eye? Or on

his forehead just below the scar I gave him for a surgery that now seems

unnecessary. Even ridiculous. Such an expensive procedure rendered futile by my

colleague in histopathology. But I had ‘scientific evidence’ to support my

decision. Not decision… recommendation; perhaps it is the same for this too is

my privilege as a physician.

One

of the greatest scientific minds ever, Einstein, defined stupidity as, ‘repeating

the same actions and somehow expecting different results’.

Einstein

should read some of today’s ‘scientific’ papers.

Einstein

also advocated that time is relative. I understand this now, for this patient's remaining time just cannot be quantified. Can you compare few weeks of

independent, healthy life with a few months of totally dependent, vegetative

state? Which one is longer?

"How much time do I

have?”

Death

is an event, but dying is a process, which starts when I answer this question.

When I don’t, the process does not start. I cannot delay death, but I can delay

dying.

Time

is indeed relative. And I certainly do not have time for this.

I

smile at him, and tell him to see the oncologist who sent him to me.

I

leave the room.

CREDITS:

About the Author: Dr. Shahzad

Shamim

is a practicing Neurosurgeon with primary interest in Neuro-Oncology.

About the Reviewer / Editor: Dr. Rija Rehan, AKU MBBS Class of 2015, is a budding psychiatrist. She's

also interested in performing arts, astronomy, literature, singing badly

and celebrating the many beauties of life.

Illustration / Photo-credit: Saniya

Kamal, AKU MBBS Class of 2018, is curious about life, the

universe, and everything in between. She hopes to become a neurologist, pursue

art, popularize meta-fiction, conquer the world and stay happy.

Editorial Note: This is from a series

collected as part of the Narrative Medicine Workshop at AKU on January 20th,

2016. The editorial work was performed by The

Writers’ Guild, an interest group at AKU, with the purpose to promote love

of reflective reading and writing, within and outside of AKU.

DISCLAIMER: Copyright belongs to the author. This blog cannot be held responsible for events bearing overt resemblance to any actual occurrences.

DISCLAIMER: Copyright belongs to the author. This blog cannot be held responsible for events bearing overt resemblance to any actual occurrences.

Comments

Post a Comment