Health Innovation the CRISPR way

"Guys Google #crisper baby", a young colleague texted the

team.

The

Googling didn’t take long to make me realize the spelling error. The word was

meant to be CRISPR (pronounced “crisper”),

alluding to the cutting edge genomic editing technology that had taken the

world by storm. The human baby (or babies, twins Lulu and Nana, to be more

precise, as I learned later) created in China using CRISPR had created a lot of

excitement, and not necessarily the good kind. The births occurred late last

year so you may think this is not newsworthy anymore. I believe it is equally

important now, given the continuing after effects; just one case in point is it

being referred to the ‘CRISPR baby scandal’ by the very prestigious journal

Nature.

The

Googling didn’t take long to make me realize the spelling error. The word was

meant to be CRISPR (pronounced “crisper”),

alluding to the cutting edge genomic editing technology that had taken the

world by storm. The human baby (or babies, twins Lulu and Nana, to be more

precise, as I learned later) created in China using CRISPR had created a lot of

excitement, and not necessarily the good kind. The births occurred late last

year so you may think this is not newsworthy anymore. I believe it is equally

important now, given the continuing after effects; just one case in point is it

being referred to the ‘CRISPR baby scandal’ by the very prestigious journal

Nature.

At

first, I didn’t realize the misspelling. In the heat of the moment (no pun

intended), I thought the term ‘crisper

baby’ was referring to some burn-related injury. The fact that I’m a

pediatric emergency physician likely informed that pseudo-deduction.

“Not only is the victim a baby, the ‘hashtag crisper

baby’ meme is even more unfortunate”, I thought.

Although

I wouldn’t put it past social media or tabloids to come up with such

cringe-worthy titles, I was intrigued.

Whenever

I’m asked by my post-millennial team to Google something, I generally comply.

Likely because of my #FOMO (and for the uninitiated in such 3-4 letter

acronyms, that stands for ‘Fear Of Missing Out’).

The

Googling didn’t take long to make me realize the spelling error. The word was

meant to be CRISPR (pronounced “crisper”),

alluding to the cutting edge genomic editing technology that had taken the

world by storm. The human baby (or babies, twins Lulu and Nana, to be more

precise, as I learned later) created in China using CRISPR had created a lot of

excitement, and not necessarily the good kind. The births occurred late last

year so you may think this is not newsworthy anymore. I believe it is equally

important now, given the continuing after effects; just one case in point is it

being referred to the ‘CRISPR baby scandal’ by the very prestigious journal

Nature.

The

Googling didn’t take long to make me realize the spelling error. The word was

meant to be CRISPR (pronounced “crisper”),

alluding to the cutting edge genomic editing technology that had taken the

world by storm. The human baby (or babies, twins Lulu and Nana, to be more

precise, as I learned later) created in China using CRISPR had created a lot of

excitement, and not necessarily the good kind. The births occurred late last

year so you may think this is not newsworthy anymore. I believe it is equally

important now, given the continuing after effects; just one case in point is it

being referred to the ‘CRISPR baby scandal’ by the very prestigious journal

Nature.

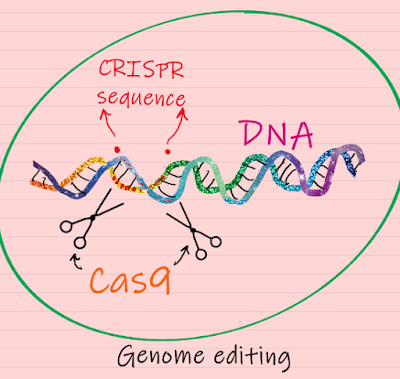

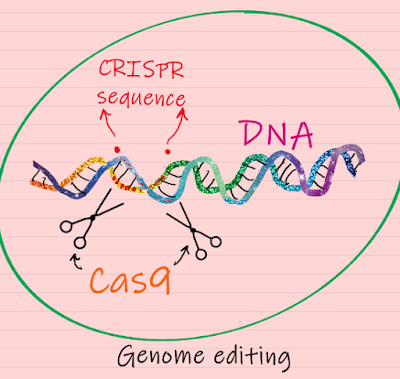

Prior

to delving into the ethical debate around it, let me explain what CRISPR is and

does. CRISPR stands for

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats. These are special

DNA sequences originally discovered in bacterial genomes. CRISPR works in

conjunction with a protein called Cas9 (or ‘CRISPR-associated protein 9’), an

enzyme that acts like a pair of molecular scissors that can cut strands of DNA.

Taken together, the CRISPR-Cas9 system constitutes a simple, yet powerful

editing tool for any genome. It allows researchers to easily alter DNA, which may

then lead to modification of gene function. Going into further details of how

this system works will be beyond the scope of this blog, but there are

excellent credible resources that one can access through the web, if interested

in learning further.

Gene editing has great

potential in both treating and preventing diseases that are either single gene

disorders or those that show more complex inheritance patterns. A few examples

of the former for which research is ongoing include cystic fibrosis, hemophilia

and sickle cell anemia. From the more complex disease category, there is

potential to tackle various cancers, mental illness, heart disease, and HIV

infection. The research studies tend to focus on cells and animal models. They

have not employed patients in large clinical trials as yet. But this area is

opening up. For instance, here’s one scenario: a young woman with a strong

family history of breast cancer known to carry a mutation in the BRCA1 gene

(linked with breast cancer) opts for CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene editing through

a gene therapy clinical trial. Although this may not be science fact as yet, it

may not be too far off in the distant future.

Techniques for modifying

genomes have existed for several decades. However, recent innovations around the

technology have enabled faster, more efficient and cheaper approaches. Through

research, this field of applied biology has been prevalent in non-humans, i.e.,

‘model organisms’ such as yeast, bacteria and mice, in the pre-clinical

laboratory setting. However, the popular media only tends to take more notice

when potential usage in humans is under consideration.

As the science of genome

editing gathers momentum, so does the ethics of it. The beneficial aspect of

treating or preventing human disease using gene editing in adult somatic (or

body) cells may be self-evident. The dilemma arises when germline DNA editing

is considered. Germline refers to the reproductive cells, i.e. the sperm and

egg. Tinkering of germline DNA through gene editing means that the altered DNA

will be transmitted to future generations. The scenario of ‘genomic enhancement’ using CRISPR-Cas9 technology will not be far

behind. In other words, parents-to-be who have the money for it, will opt to

genetically enhance their babies who on top of zero likelihood of certain

genetic disorders, will have enhanced features based on mere parental whims, such as

color of skin, height, ‘beauty’ / cosmetic features, etc.

The general consensus of the

scientific and non-scientific communities alike is that we are nowhere close to

an understanding of the technology and what it can do, to give it a green

signal at this stage, either scientifically or ethically. However, what has

happened in China with the twins being products of gene-edited germline DNA, we

may have to propel this discussion ahead. We need to pause and ponder what are

we really getting into?

In the late 90s, as Y2K was

approaching, rather than being depressed about the world coming to an end, I

was really excited. I was a graduate student in human genetics and at that time

the Human Genome Project was in full swing. I was quite full of the young

physician-scientist’s chutzpah that complete knowledge of our genetic heritage and

subsequent gene therapy successes would be the panacea that the world was

seeking. Although I was lured by the love of genes and genomes, there was

something lacking towards the end of my graduate studies that precluded my

continued work in the field of genetics. I was impatient and I felt that the

speed of progress then, using genomics as a tool, was just not fast enough for

me.

Now

that I’m older and hopefully wiser, I think I tend to be more nuanced in my

approach to scientific hype. I used to get energized thinking about genomics, gene

therapy, stem cells, and such. A decade or two later, I feel the same is happening

with data science, artificial intelligence, machine learning, and the latest

craze, genomic editing. CRISPR may be a real game changer per some

proponents of the technology. Perhaps they have their own vested interests in

extolling this as the next molecular revolution. However, there is still so

much to learn and understand about CRISPR and what it can or cannot deliver,

that cautious optimism should be the order of the day. Slow and steady, prudent

progress in this field will likely go a lot further in pushing the envelope on

health innovation for the betterment of humanity the world over.

[from Health & Disease]

Acknowledgment: Author acknowledges Haider Ali and Rayaan Mian for critically reviewing and editing this essay.

I read your whole article it is really helpful for me and others. the points you described above about

ReplyDeleteeyes and its health Kjolberg is very helpful for everyone. After reading these points I am blessed to have this blog. I appreciate your work and knowledge. I will recommend this content to others, more people will get the information and help. Thanks!

Myopia is one of the most common eye problems faced by people around the world. Myopia can lead to high blindness. So regular and timely eye check up is important to better prevent and manage eye conditions. Eye Exam Singapore

ReplyDelete